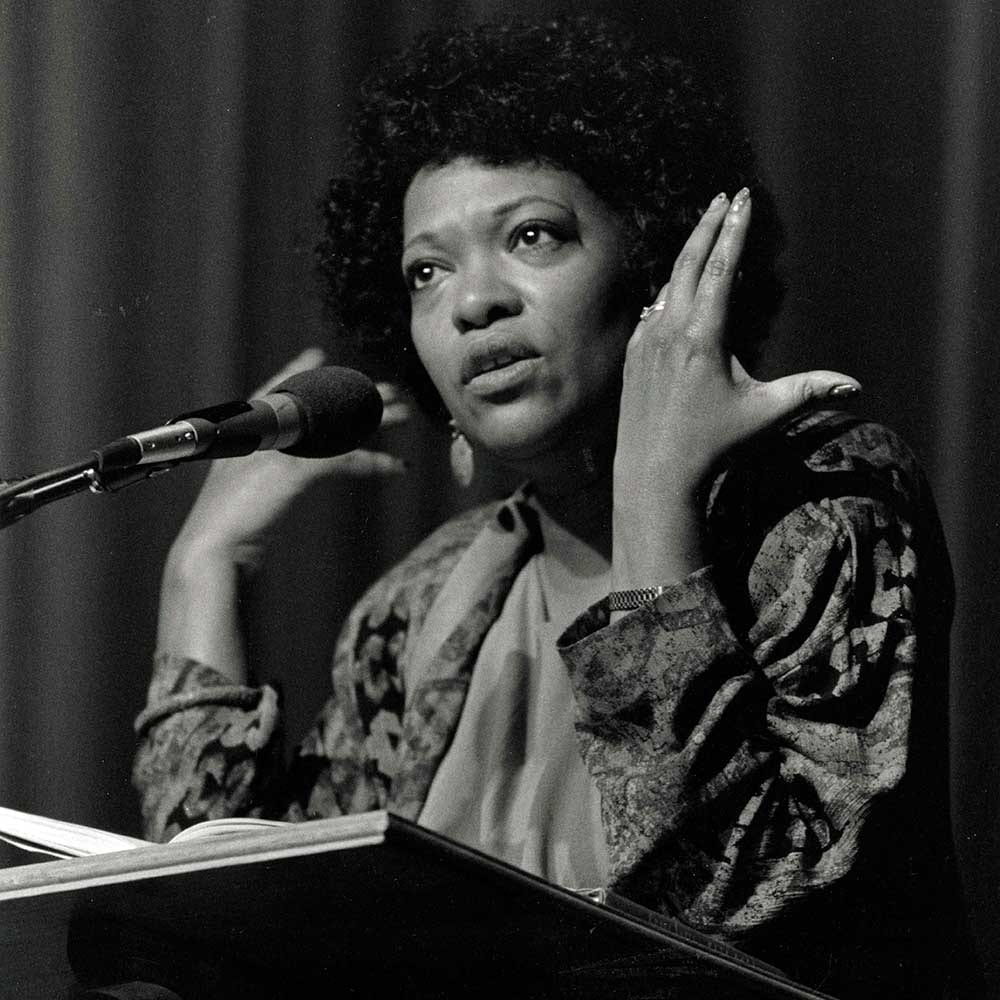

Rita Dove

“This is love. And this is where I need to be.”

At the time of the 1994 conference, Rita Dove had just been named Poet Laureate of the United States, and had recently published a novel, Through the Ivory Gate(1992), which accompanied her acclaimed books of poetry: The Yellow House on the Corner (1980); Museum (1983); Grace Notes (1989); and Thomas and Beulah (1986), which earned her a Pulitzer Prize. Other books now include Mother Love (1995), On the Bus With Rosa Parks (1999), American Smooth (2004), Sonata Mulattica (2009), and Collected Poems: 1974-2004 (2016), a National Book Award finalist, as well as Fifth Sunday (1985), a collection of short stories, The Darker Face of the Earth (1994), a play, and The Poet’s World (1995), a book of essays. Dove served as Poet Laureate of the Commonwealth of Virginia from 2004 to 2006, and has received countless awards and honors, such as a Duke Ellington Lifetime Achievement Award, the Barnes & Noble Writers for Writers Award, a Library of Virginia’s Lifetime Achievement Award, a Fulbright Lifetime Achievement Medal, and a National Humanities Medal presented to her by President Bill Clinton. In 2011, President Barack Obama also presented her with a National Medal of Arts, making her the only poet to have received both distinctions. Dove was also awarded a Furious Flower Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014. Dove has been the editor of two anthologies, The Best American Poetry 2000 (2000) and The Penguin Anthology of Twentieth-Century American Poetry (2011), and was named Poetry Editor of The New York Times Magazine in 2018.

Featured Poems

“Parsley”

“Agosta the Winged Man and Rasha the Black Dove”

Interviews, Talks, and Readings

/ Rita Dove reads “Parsley”

- The Cane Fields

There is a parrot imitating spring

in the palace, its feathers parsley green.

Out of the swamp the cane appears

to haunt us, and we cut it down. El General

searches for a word; he is all the world

there is. Like a parrot imitating spring,

we lie down screaming as rain punches through

and we come up green. We cannot speak an R—

out of the swamp, the cane appears

and then the mountain we call in whispers Katalina.

The children gnaw their teeth to arrowheads.

There is a parrot imitating spring.

El General has found his word: perejil.

Who says it, lives. He laughs, teeth shining

out of the swamp. The cane appears

in our dreams, lashed by wind and streaming.

And we lie down. For every drop of blood

there is a parrot imitating spring.

Out of the swamp the cane appears.

- The Palace

The word the general’s chosen is parsley.

It is fall, when thoughts turn

to love and death; the general thinks

of his mother, how she died in the fall

and he planted her walking cane at the grave

and it flowered, each spring stolidly forming

four-star blossoms. The general

pulls on his boots, he stomps to

her room in the palace, the one without

curtains, the one with a parrot

in a brass ring. As he paces he wonders

Who can I kill today. And for a moment

the little knot of screams

is still. The parrot, who has traveled

all the way from Australia in an ivory

cage, is, coy as a widow, practising

spring. Ever since the morning

his mother collapsed in the kitchen

while baking skull-shaped candies

for the Day of the Dead, the general

has hated sweets. He orders pastries

brought up for the bird; they arrive

dusted with sugar on a bed of lace.

The knot in his throat starts to twitch;

he sees his boots the first day in battle

splashed with mud and urine

as a soldier falls at his feet amazed—

how stupid he looked!— at the sound

of artillery. I never thought it would sing

the soldier said, and died. Now

the general sees the fields of sugar

cane, lashed by rain and streaming.

He sees his mother’s smile, the teeth

gnawed to arrowheads. He hears

the Haitians sing without R’s

as they swing the great machetes:

Katalina, they sing, Katalina,

mi madle, mi amol en muelte. God knows

his mother was no stupid woman; she

could roll an R like a queen. Even

a parrot can roll an R! In the bare room

the bright feathers arch in a parody

of greenery, as the last pale crumbs

disappear under the blackened tongue. Someone

calls out his name in a voice

so like his mother’s, a startled tear

splashes the tip of his right boot.

My mother, my love in death.

The general remembers the tiny green sprigs

men of his village wore in their capes

to honor the birth of a son. He will

order many, this time, to be killed

for a single, beautiful word.

/ Rita Dove reads “Agosta the Winged Man and Rasha the Black Dove”

the boa constrictor

coiled counterwise its

heavy love. How

the spectators gawked, exhaling

beer and sour herring sighs.

When the tent lights dimmed,

Rasha went back to her trailer and plucked

a chicken for dinner

The canvas,

not his eye, was merciless.

He remembered Katja the Russian

aristocrat, late

for every sitting,

still fleeing

the October Revolution –

how she clutched her sides

and said not

one word. Whereas Agosta

(the doorbell rang)

was always on time, lip curled

as he spoke in wonder of women

Trailing Schad paced the length of his studio

and stopped at the wall,

staring

at a blank space. Behind him

the clang and hum of Hardenbergstrasse, its

automobiles and organ grinders.

Quarter to five.

His eyes traveled

to the plaster scrollwork

on the ceiling. Did that

hold back heaven?

He could not leave his skin – once

he’d painted himself in a new one,

silk green, worn

like a shirt.

He thought

of Rasha, so far from Madagascar,

turning slowly in place as

backstage to offer him

the consummate bloom of their lust.

Schad would place him

on a throne, a white sheet tucked

over his loins, the black suit jacket

thrown off like a cloak.

Agosta had told him

of the medical students

at the Charite

that chill arena

where he perched on

a cot, his torso

exposed, its crests and fins

a colony of birds trying

to get out . . .

and the students

lumps caught

in their throats, taking notes.

Ah, Rasha’s

foot on the stair.

She moved slowly, as if she carried

the snake around her body

always.

once

she brought fresh eggs into

the studio, flecked and

warm as breath

Agosta in

classical drapery, then,

and Rasha at his feet.

Without passion. Not

the canvas

but their gaze,

so calm,

was merciless.

Related Links

Interactive Program Day II

Collection Highlights

Timeline: History, Witness, and the Struggle for Freedom in African American Poetry